Ultra-Processed Foods and Your Health: What the Science Says

This article is part of our comprehensive guide on The Complete Guide to Food Processing. Read the full guide for a complete overview of the topic.

If you've ever wondered why that bag of chips seems impossible to put down or why you feel hungry shortly after eating a processed meal, you're experiencing the engineered effects of ultra-processed foods (UPFs).

Our comprehensive Complete Guide to Food Processing explains the different levels of processing, but here we'll dive deep into the specific health impacts that make UPFs uniquely problematic for human health.

🧠 The Engineered Problem

Why UPFs Bypass Natural Satiety

Ultra-processed foods are specifically designed to override your body's natural hunger and satiety signals. Unlike whole foods that trigger complex hormonal responses telling your brain you're full, UPFs are engineered to be hyperpalatable—a combination of salt, sugar, fat, and texture that activates reward pathways in your brain similar to addictive substances.

🎯 The Hyperpalatability Factor

Food scientists use what's called the "bliss point"—the precise combination of sugar, salt, and fat that maximizes pleasure and keeps you eating. This isn't accidental; it's the result of extensive research and testing to create foods that are literally irresistible.

How UPFs Override Satiety:

- • Rapid consumption: Soft textures require minimal chewing, allowing fast intake before fullness signals register

- • Calorie density: High calories packed into small volumes bypass natural portion control

- • Reward hijacking: Artificial flavors trigger dopamine release without nutritional satisfaction

- • Texture engineering: Specific mouthfeel combinations enhance palatability beyond natural foods

📊 The Weight Gain Connection

Clinical Evidence

The most compelling evidence comes from a landmark 2019 study by Dr. Kevin Hall at the National Institutes of Health. In this carefully controlled clinical trial, participants eating ultra-processed diets consumed an average of 508 more calories per day compared to when eating unprocessed foods—even though both diets were matched for calories, sugar, fat, fiber, and macronutrients.

The Hall Study Findings

Participants on the ultra-processed diet gained 2 pounds in just two weeks, while those eating unprocessed foods lost 2 pounds. This wasn't due to willpower or conscious choices—it was the direct result of how these foods interact with our biology.

Key Insight: The problem isn't just the nutrients in ultra-processed foods—it's how the processing itself changes how our bodies respond to those nutrients. Even when calories and nutrients are matched, ultra-processed foods lead to overeating and weight gain.

🎭 Chronic Disease Links

The Growing Evidence

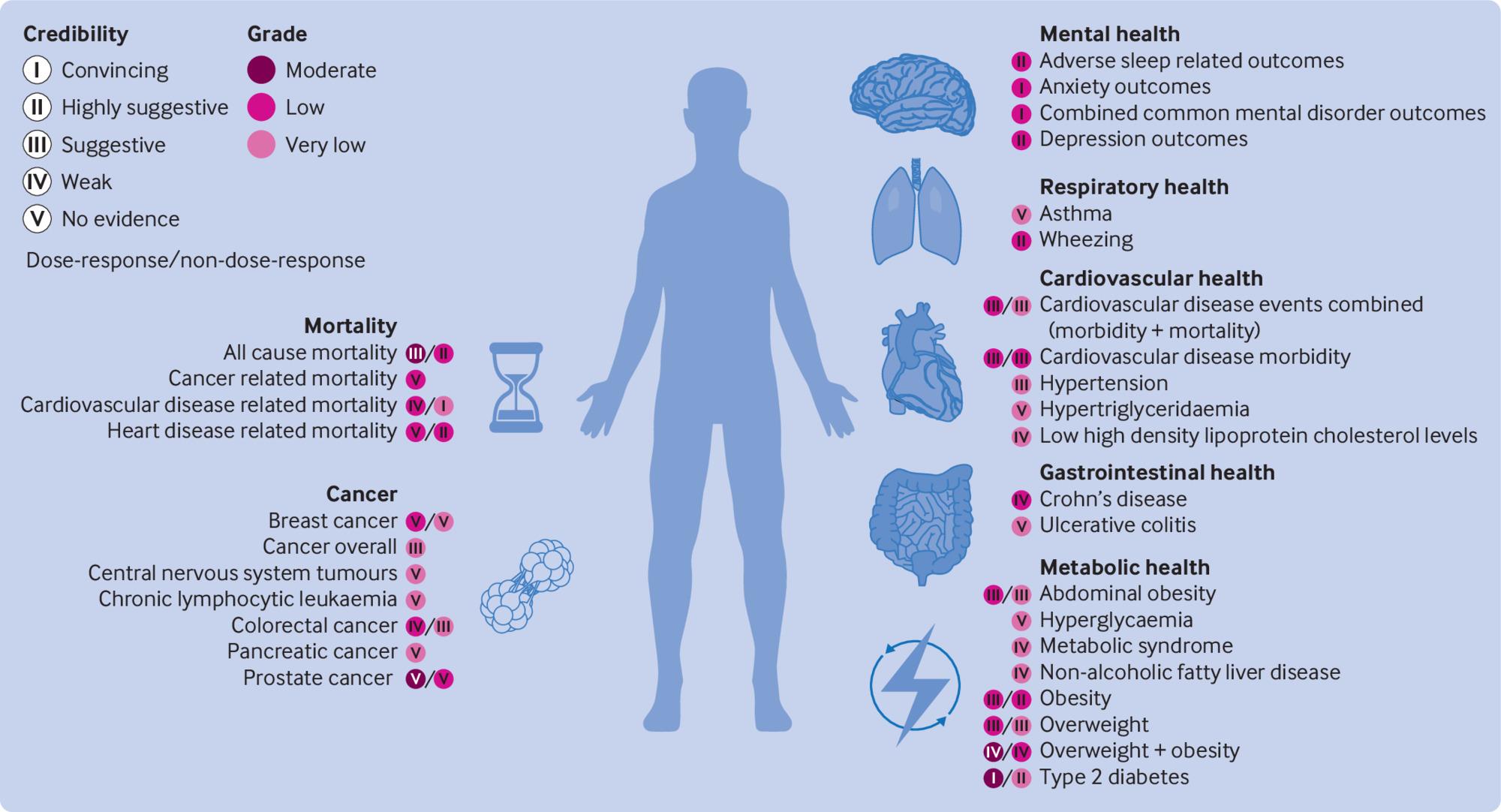

Beyond weight gain, large-scale population studies consistently link high ultra-processed food consumption to increased risks of serious chronic diseases. The evidence is particularly strong for cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and certain cancers.

Cardiovascular Disease

A major 2019 study following over 105,000 French adults found that each 10% increase in ultra-processed food consumption was associated with a 12% increase in cardiovascular disease risk. This relationship held even after accounting for other dietary factors and lifestyle variables.

Type 2 Diabetes

Research tracking over 100,000 participants found that those consuming the most ultra-processed foods had a 15% higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes compared to those eating the least. The mechanisms likely involve blood sugar spikes, inflammation, and disrupted insulin sensitivity.

Cancer Risk

Ultra-processed food consumption has been linked to increased risks of colorectal and breast cancers. While the exact mechanisms aren't fully understood, potential factors include harmful compounds formed during processing, packaging chemicals, and the displacement of protective whole foods from the diet.

The Gut Microbiome Disruption

One of the most concerning aspects of ultra-processed foods is their impact on gut health. Your gut microbiome—the trillions of bacteria living in your digestive system—plays crucial roles in immunity, mood regulation, and overall health.

How UPFs Harm Gut Bacteria

Harmful Effects:

- • Emulsifiers can damage intestinal barrier function

- • Artificial sweeteners may reduce beneficial bacteria

- • Preservatives are designed to kill microorganisms (including good ones)

- • Lack of fiber starves beneficial microbes

Health Consequences:

- • Increased intestinal permeability ("leaky gut")

- • Chronic low-grade inflammation

- • Weakened immune function

- • Potential mood and cognitive effects

Mental Health and Cognitive Effects

Emerging research suggests that ultra-processed foods may also affect mental health and cognitive function. Studies have found associations between high UPF consumption and increased rates of depression, anxiety, and cognitive decline.

The Brain-Gut Connection

The gut microbiome communicates directly with the brain through the vagus nerve and by producing neurotransmitters like serotonin. When ultra-processed foods disrupt gut health, they may indirectly affect mood and mental clarity.

The Addiction-Like Response

Brain imaging studies show that ultra-processed foods activate reward pathways similar to addictive substances. This neurological response helps explain why these foods can feel genuinely difficult to resist and why some people experience withdrawal-like symptoms when reducing UPF consumption.

Signs of Food Addiction-Like Behavior:

- • Inability to stop eating despite feeling full

- • Cravings for specific processed foods

- • Eating in secret or feeling shame about food choices

- • Using food to cope with emotions

- • Continued eating despite negative health consequences

Individual Variation and Vulnerability

While ultra-processed foods affect everyone, some people may be more vulnerable to their effects. Factors that may increase susceptibility include genetics, stress levels, sleep quality, existing gut health, and previous diet history.

Children and Adolescents

Young people may be particularly vulnerable because their brains are still developing, their eating habits are forming, and they're exposed to aggressive marketing of ultra-processed foods. Early exposure to UPFs may set up lifelong patterns of overconsumption.

The Path Forward: Practical Protection Strategies

Understanding the health impacts of ultra-processed foods isn't meant to create fear—it's meant to empower informed choices. You don't need to eliminate all processed foods to protect your health.

Focus on Food Replacement, Not Restriction

Rather than focusing on what to avoid, emphasize adding more whole foods to crowd out ultra-processed options. When you fill up on nutritious, satisfying whole foods, you naturally have less room and desire for ultra-processed alternatives.

Practical Steps:

- • Start meals with fiber-rich foods (vegetables, fruits, whole grains)

- • Include protein and healthy fats to enhance satiety

- • Plan satisfying whole food snacks

- • Gradually reduce UPF consumption rather than eliminating completely

- • Focus on foods that make you feel energized and satisfied

Hope and Recovery

The good news is that many of the negative effects of ultra-processed foods can be reversed. When people reduce UPF consumption and increase whole food intake, they often experience:

- • Improved appetite regulation within days to weeks

- • Better energy levels and mood stability

- • Gradual weight normalization

- • Reduced cravings for hyperpalatable foods

- • Improved gut health and digestion

Your body has remarkable healing capacity when given the right conditions. By understanding how ultra-processed foods affect your health and making gradual, sustainable changes toward whole foods, you can reclaim control over your eating patterns and support your long-term wellbeing.

For more comprehensive information about food processing levels and practical strategies for healthier eating, explore our complete guide to food processing.

Scientific References

This article is based on peer-reviewed research and scientific evidence. Below are key studies that support the information presented about ultra-processed foods and health.

Key Research Papers:

1. Hall, K. D., Ayuketah, A., Brychta, R., et al. (2019).Ultra-processed diets cause excess calorie intake and weight gain: an inpatient randomized controlled trial of ad libitum food intake. Cell Metabolism, 30(1), 67-77.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.05.008

Note: The landmark NIH clinical trial showing UPFs cause overeating and weight gain.

2. Srour, B., Fezeu, L. K., Kesse-Guyot, E., et al. (2019).Ultra-processed food intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: prospective cohort study (NutriNet-Santé). BMJ, 365, l1451. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l1451

Note: Large French cohort study linking UPF consumption to cardiovascular disease risk.

3. Lane, M. M., et al. (2024).Ultra-processed food exposure and adverse health outcomes: umbrella review of epidemiological meta-analyses. BMJ, 384, e077310. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2023-077310

Note: Comprehensive umbrella review synthesizing evidence from multiple meta-analyses on UPF health effects.

4. Chassaing, B., Koren, O., Goodrich, J. K., et al. (2015).Dietary emulsifiers impact the mouse gut microbiota promoting colitis and metabolic syndrome. Nature, 519(7541), 92-96. doi: 10.1038/nature14232

Note: Foundational research showing how UPF emulsifiers can disrupt gut microbiome and promote inflammation.

5. Fiolet, T., Srour, B., Sellem, L., et al. (2018).Consumption of ultra-processed foods and cancer risk: results from NutriNet-Santé prospective cohort. BMJ, 360, k322. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k322

Note: Key study linking ultra-processed food consumption to increased cancer risk.

6. Fagherazzi, G., et al. (2019).Consumption of ultra-processed foods and risk of type 2 diabetes: results from three large prospective French cohorts. Diabetes Care, 42(12), 2313-2320. doi: 10.2337/dc19-0827

Note: Evidence linking UPF consumption to type 2 diabetes development.

Note: This information is for educational purposes and should not replace professional medical advice. Always consult with healthcare providers for personalized dietary recommendations.

Want to Learn More?

This is just one aspect of the complete guide to food processing. Explore our comprehensive guide for more insights.

Read the Complete Guide